The South has been the driving force for United States population growth in recent years – in 2023 for example, the region accounted for 87% of the nation’s population growth,

That population growth has helped spur economic growth in that region. But the changing climate may turn that equation on its head.

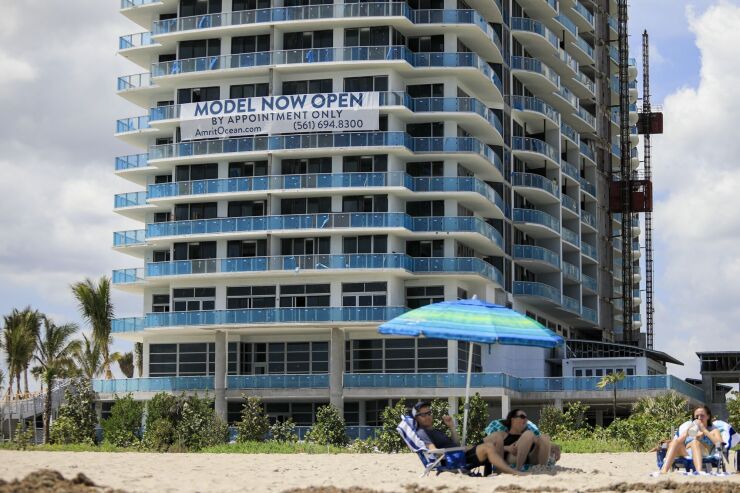

People moving to the South, often in pursuit of lower housing costs and taxes, may be running into a climate-change driven buzzsaw.

Bloomberg News

In a February 2023 report,

The list of cities facing acute risks is a highlight reel of places drawing population growth, starting in the Carolinas.

The report said the cities facing the most acute risk will be Jacksonville, New Bern, Wilmington, and Greenville, in North Carolina, and Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. The states facing the most acute risk will be Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Delaware.

The cities with the most chronic physical risk will be San Francisco; Cape Coral, Florida; New York City; Long Island in New York, which the report treats as a city; and Oakland, California.

As actuaries try to measure the risks climate change is adding in those places, the result is apt to be property insurance sticker shock as insurers stop doing business

“The insurance industry is affecting the affordability of U.S. cities as they make significant changes to coverage options in communities they deem high risk,” said Amy Bailey, director of climate resilience and sustainability at the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions.

Indeed, several insurers have pulled

Home insurance rates rose by 10% in 19 states in 2023 according to Insurance Information Institute analysis of data from S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Real estate company Redfin

Louisiana has also seen rapidly rising home insurance rates because of climate change. Redfin data says that homes that went under contract in New Orleans in February had an average stay on market of 97 days, the longest of any U.S. major metropolitan area, perhaps reflecting increasing home insurance rates.

Problems with increasing insurance costs in Florida and Louisiana have the possibility of disrupting the property finance market, Bola Kushimo, a Moody’s Ratings vice president and senior credit officer said

Since 60% of local government revenue comes from property and sales taxes, this may potentially be a problem in the future, Kushimo said.

In April, S&P Global Ratings released a report on how it expected climate change to affect the United States, with a focus on projections for the 2050s. The report predicted 45% more extreme heat days and 50% more days with wildfires nationally by that decade.

Hawaii and localities in the West, Southwest, and Southeast will be most exposed to extreme heat conditions.

“Many of the most exposed localities to drought hazards include areas with high agricultural output,” the report said. “These include Iowa, Indiana, Illinois, and Nebraska.”

Drought is expected to be an increasingly common problem, mainly west of the Mississippi, the report said. New Mexico, Colorado and Arizona are the states that combine the most exposure to extreme heat and water stress.

California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas are anticipated to be the states with the greatest wildfire exposure.

By 2050 flooding due to sea level rise is expected to increase in frequency by four times in the Gulf States and about three times on the East Coast, both excepting Florida. Other states should see increases below three times. These estimates assume there are no adaptation measures taken.

Louisiana is expected to have the most serious exposure to coastal flooding in the United States, the report said.

Additionally, by the 2050s in the nation river-basin flooding and heavy-rainfall related flooding are expected to rise by 31% and 24% respectively.

In March, the journal Nature published a study on the impact of rising sea levels and coastal subsidence on 32 coastal U.S. cities from Massachusetts through northern California. Cities north of California were ignored because of a lack of data and north of Massachusetts because of their comparatively small size. The study did not look at Alaska, Hawaii or the territories.

The article’s authors found a further land area of 388 square miles to 536 square miles in these cities will be “threatened” by relative sea-level rise by 2050. This would pose a threat to 55,000-273,000 people and 31,000-171,000 properties. The cities currently have about 25 million residents.

The projections assume the cities do not construct additional flood defense structures.

The maximum population and property exposure by 2050 represents approximately one in 50 people and one in 35 properties in the cities, the authors said.

Miami, with an average elevation of less than six feet above sea level, would account for 38%-44% of East Coast city exposed land.

New Orleans would be an even greater portion of Gulf Coast urban risk. This assumes no flood protection, even though the authors acknowledge New Orleans has some of this. However, “flood control systems may only represent a temporary solution.” The flood protection system failed in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina struck, leading to 1,836 deaths, many of them in the city.

But efforts to combat climate change are often

Bloomberg News

According to the Moody’s Analytics report, the states whose economies would be most adversely affected by an early and aggressive federal policy against climate change would be Alaska, Oklahoma, New Mexico, North Dakota, and Wyoming. The state’s economies would be hurt by sharp curbs on fossil fuels because the states have large sectors producing those fuels.

Despite this, some cities have already spent years planning for climate change, Bailey said.

Cliff Majersik, senior advisor at the Institute for Market Transformation, said some cities are trying to reduce all sectors’ emissions, not just those from city government. They are doing inventories of the sources of greenhouse gasses. Some have a 50% cut goal. The Institute for Market Transformation is a nonprofit that spotlights business practices and public policies that improve United States buildings.

Peyton Siler-Jones, sustainability program manager at National League of Cities, said many cities are trying to cut these emissions by 80% by 2050 or sooner.

At least 130 cities in the U.S. are planning or pursuing climate-change related projects, CDP North America Associate Director Richard Freund said. CDP is an international nonprofit that oversees the largest climate disclosure process for entities besides national governments.

In March,

In an interview, Breckinridge research analyst Erika Smull said she expected these cities in the next few years to ramp up capital spending to address climate risks. She said more than half of the money for the spending was likely to come from the sale of municipal bonds.

To deal with climate change there will need to be new municipal financing structures, according to Municipal Market Analytics, Inc. President Tom Doe. His firm is projecting that climate change could push annual new-money issuance to $500 billion or more annually in just a few years, up from the total overall issuance – including refundings – of about $400 billion that has averaged the past few years.

In mid-January, Doe told a congressional committee that in coming years

Columbia, Missouri, Mayor Barbara Buffaloe said some city governments will be asking voters to approve more fees to support capital projects directly,or through bonds indirectly.

Colin Wellenkamp, executive director of Mississippi Rivers, Cities and Towns Initiative, said he believed climate-related bond issuance may have declined in the last two years – along with overall muni issuance – partly because of the rising interest rate environment and partly because the federal government has provided free and low-interest money as alternatives. The Mississippi Rivers, Cities and Towns Initiative is a group that seeks watershed-wide approaches to attracting financing for flood adaptation and other resilience measures.

Wellenkamp noted the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 provides grants and low-interest loans to municipalities to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to address climate change’s impacts.

With these options available, Wellenkamp said cities and counties see municipal bonds as second or third options to get the work done. However, when the Inflation Reduction Act money ends that will change. While it is currently scheduled to end in 2028, political changes in Washington, D.C. could end it sooner, he said.